Diagnosing PCD

Historically, the diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) has been challenging, relying heavily on the interpretation of ciliary ultrastructure from respiratory epithelial biopsies.

However, recent advances in the understanding of PCD genetics and the identification of hallmark phenotypic features have significantly improved diagnostic accuracy and accessibility.

According to the North American PCD Foundation Consensus Statement, “PCD is a rare disorder; consequently, only a limited number of centers have extensive experience in the diagnosis and management of PCD. Research over the past decade has transformed diagnostic strategies, incorporating modalities such as nasal nitric oxide (nNO) measurement and genetic testing. Nonetheless, many individuals with PCD remain undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. To date, there are limited studies addressing PCD management, and no large randomized controlled trials to guide therapy…”

Because of the challenges inherent in confirming the diagnosis of PCD, the PCD Foundation strongly recommends referral to a PCD expert center for diagnosis whenever possible.“

The American Thoracic Society (ATS) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis of PCD is now publicly available via the ATS website. This rigorously developed, evidence-based document outlines current best practices for the diagnosis of PCD and addresses common clinical challenges and misconceptions encountered in the diagnostic process.

Clinical Phenotype

A detailed clinical history is the cornerstone of the diagnostic evaluation for PCD. Based on data from the Genetic Disorders of Mucociliary Clearance Consortium (GDMCC) and the PCD Foundation Consensus Guidelines, the following four features are highly suggestive of PCD:

- Persistent, often wet-sounding cough with sputum production beginning in early infancy

- Chronic nasal congestion starting in infancy, progressing to chronic rhinosinusitis

- Neonatal respiratory distress in term infants

- Laterality defects (e.g., situs inversus totalis, situs ambiguus/heterotaxy), often accompanied by congenital heart defects

Chronic otitis media with effusion and associated hearing loss (both conductive and neurogenic) is common in children with PCD and may persist into adulthood. While not independently diagnostic, its presence alongside the above features strengthens clinical suspicion.

Diagnostic Tests (Listed by Prevalence)

The tests below are presented from most commonly used to least in current clinical practice.

1. Genetic Testing

Genetic testing is a central component of the diagnostic workup. Current commercially-available panels screen for pathogenic variants in the majority of genes associated with PCD, which collectively explain approximately 75% of genetically confirmed cases. As gene-targeted therapies become available, a confirmed molecular diagnosis will become increasingly critical for guiding treatment decisions.

The PCD Foundation Consensus Statement recommends genetic testing as part of a comprehensive diagnostic strategy.

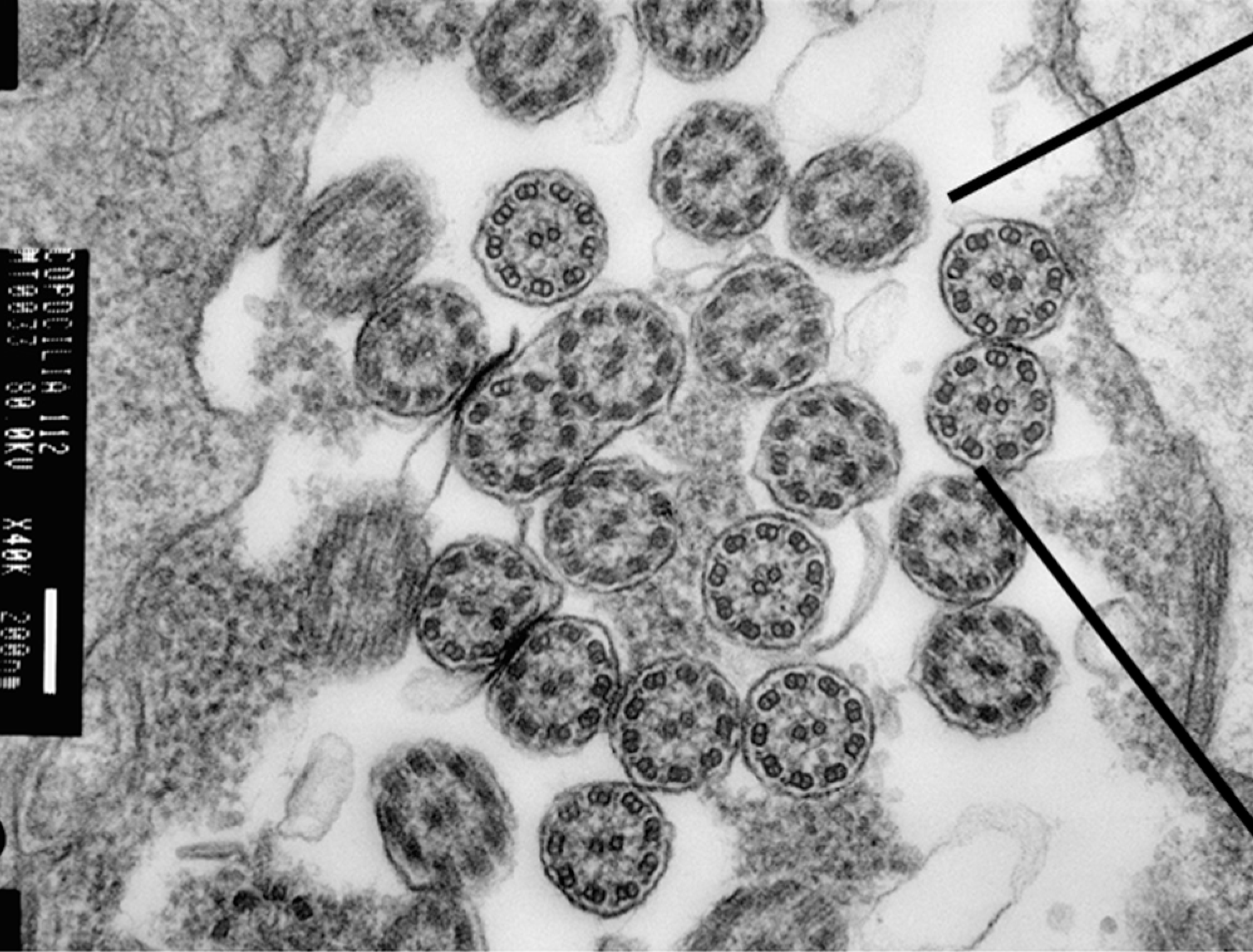

2. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

TEM remains a valuable diagnostic tool for visualizing ultrastructural ciliary defects. In recent years, international classification standards describing hallmark ciliary defects on TEM defects have been developed and validated. Characteristic findings include:

- Absence of outer dynein arms

- Combined absence of inner and outer dynein arms

- Inner dynein arm defects with microtubule disorganization

- Abnormalities in radial spokes or central apparatus

It is important to note that normal ultrastructure on TEM does not exclude PCD, as certain pathogenic variants do not produce visible defects or may cause subtle changes beyond the resolution of conventional TEM analysis.

Diagnostic yield is approximately 70% when performed under optimal conditions, though practical yield may be lower in non-specialized centers. As such, the PCD Foundation strongly recommends that TEM be performed at a PCD Foundation Clinical and Research Network Center as part of a comprehensive diagnostic workup.

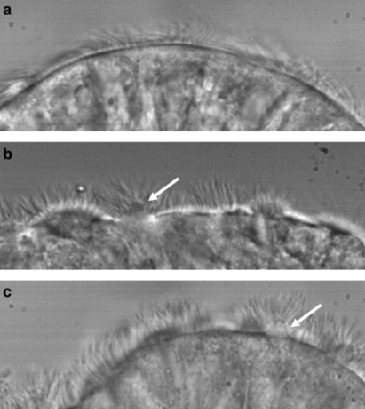

3. High-Speed Videomicroscopy (HSVM)

HSVM evaluates ciliary beat pattern and frequency using samples obtained from nasal or bronchial brushings. When performed by experienced specialists using validated SOPS, abnormal motility patterns can provide strong evidence for a PCD diagnosis. However, HSVM is highly operator-dependent; interpretation by inexperienced personnel can lead to both false positives and false negatives. In North America, HSVM is used as an adjunctive diagnostic test and in research. It is not used alone to diagnose PCD.

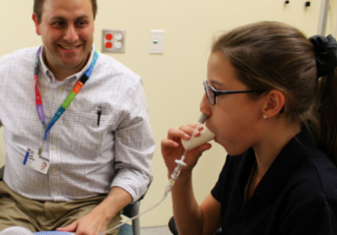

4. Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Measurement

Individuals with PCD typically have markedly reduced levels of nasal nitric oxide, a finding validated across multiple international studies. Although nNO cannot definitively confirm or rule out PCD in the U.S., it serves as a reliable screening tool when performed according to standardized protocols.

Key considerations:

- nNO is a highly sensitive screening test when administered and interpreted by trained personnel using validated methods.

- Some PCD genotypes may present with normal nNO levels.

- Cystic fibrosis must be ruled out prior to nNO testing, as individuals with CF may also exhibit low nNO.

The PCD Foundation endorses nNO testing as part of the diagnostic evaluation at its accredited clinical centers.

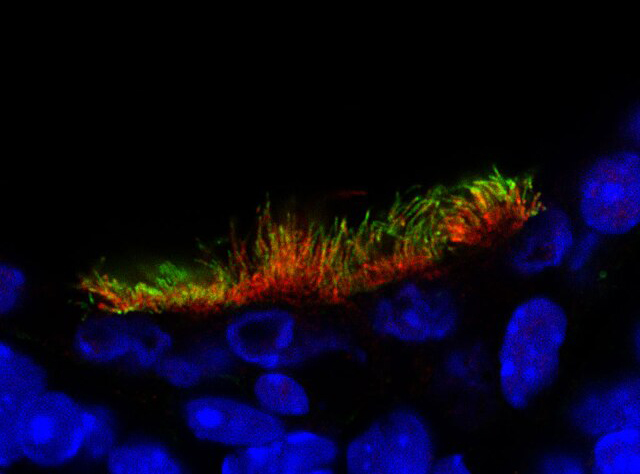

5. Immunofluorescence (IF)

IF testing utilizes antibodies to detect missing or mislocalized ciliary proteins. While it can be a useful adjunct in the diagnostic process, IF alone is insufficient to establish a definitive diagnosis and should be interpreted in conjunction with other diagnostic modalities.

Genetic Testing Resources

Genetic testing for PCD is widely available in North America. The choice of testing provider may depend on physician preference, institutional affiliation, and insurance requirements.